Descargar PDF

Justo Pastor Mellado

Art Critic, Independent Curator

Sala de Espera (Waiting Room) is an installation built by Carlos Leppe at sur Gallery in November 1980, and is composed of three mini-installations, known as (I) Las Cantatrices (The Opera Singers), (II) La Portada (The Cover) and (III) El Título (The Title) (See Site Map).

The first— Las Cantatrices —refers to four television monitors. The first three play a film of Leppe in make-up, his torso enveloped in plaster, as he lip-syncs an operatic aria through the physical intervention of an orthopedist dental apparatus, which keeps his mouth open. The fourth monitor, positioned to face the first three, plays a film of Leppe’s mother telling stories about her son’s life.

The second— La Portada —consists of three parts: a) a reproduction of the cover design for the book Cuerpo correccional (Correctional body), which features the door to Leppe’s childhood home, the steps lit by fluorescent tubes; b) a projected photograph of Leppe with his mother in a park; and c) bundles of soil, wrapped in clear plastic sheeting, reminiscent of bodies recently exhumed.

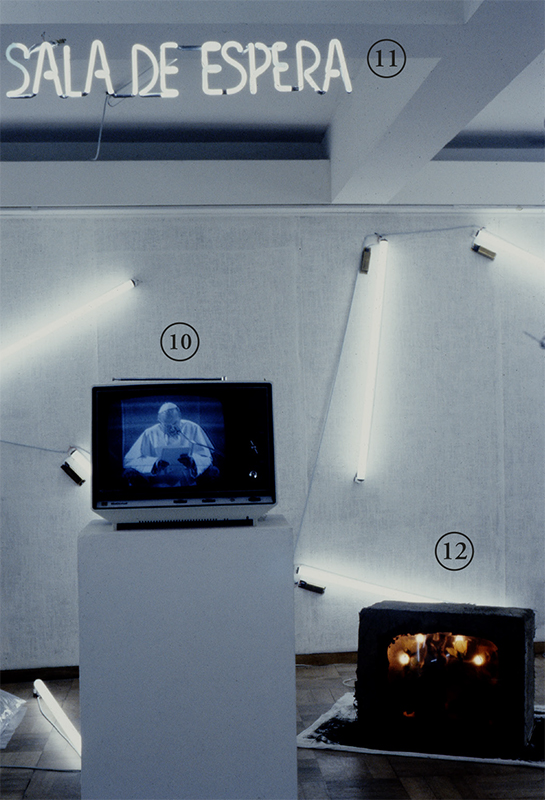

The third— El Título —brings together three final elements: a television on mute, which shows footage of the broadcast by the national TV channel; a mud block the size of a television, the interior of which holds a protective panel, forming a window that displays an image of the Immaculate Conception; and finally, the title of the work, written in neon letters.

In addition to these three scenes, Leppe distributes a network of fluorescent tubes across the floor and walls of the room, about twenty in total.

Sala de Espera is a “staging” of the written text in Cuerpo correccional, the book by Nelly Richard; the book is itself conceived as a “theoretical staging” of Leppe’s work. The video Las Cantatrices preceded both installation and the book, playing a fundamental generative role in the collaboration between Leppe and Richard.

1- Stand on which Leppe installs a slide projector, with a single image in the carrel. The image will be projected against the screen on the facing wall.

2- On the back wall, two graphic elements: a) to the left, the reproduction of a text (unidentified); and b) a photograph of an installation (the intervention Carlos Leppe made on the steps of his mother’s house).

3- Scattered across the same walls: fluorescent tubes torn from their support frames and exhibited with their voltage transformers.

4- Monitor set on a hospital table, with its respective playback machine. The image shows the mother of Leppe telling a story, the complete text of which appears in Nelly Richard’s aforementioned book. The lower section of the television is covered by a strip of medical gauze.

5- Scattered across the floor: fluorescent tubes, mounted in the same conditions as described above.

6- Same object as indicated in 4.

7- On the floor, among three fluorescent tubes and in front of a screen, Leppe arranges five plastic sacks, filled with soil.

8- Slide projection screen, on which Leppe projects a single photograph, where he appears seated on the grass in a park, with his mother. This photograph is also reproduced in the supplement La Separata, Nº 1, April 16 1981, sur Gallery, Santiago de Chile.

9- On the wall, 7 fluorescent tubes mounted in the manner described above.

10- On a stand, an IRT television plays footage pope from the national broadcasting channel (Television Nacional de Chile, TVN), with the sound off.

11- The title of the work, Sala de Espera, in neon letters.

12- Mud block with tubes of cathode lights.

13- A hollowed block, made of mud and straw, with an aperture on one of its sides, through which a cathode light tube is embedded. The interior, which has been emptied of its contents, instead contains—like a roadside shrine—a plaster figurine of the Immaculate Conception, surrounded by a garland of light.

14- Three hospital tables hold three televisions, all in use as video monitors, with their respective playback mechanisms arranged on the floor. Each of them reproduce sections of an opera piece out-of-sync with Leppe’s mouthed vocals. The sound from each television impacts the audibility of the one next to it. A fourth monitor, facing the others, plays a video of Leppe’s mother, in a close-up shot, telling the story. The sound from all four monitors are heard simultaneously, at a medium volume.

15- Image of the fourth monitor from Las Cantatrices, which shows a video of Leppe’s mother.

Carlos was born in the morning, on October 9, 1952, at ten minutes to seven. He could’ve not been born. I’m not sure how he was. The doctor wanted me to have a normal birth because his mind was somewhere else, believing I had a more active married life. Anyway I didn’t dilate one bit and suffered worse than you can imagine. I was losing blood and the baby wasn’t coming out. If I’d known what I was going to suffer I wouldn’t have gotten married for anything. But I always want things to be unique. He ate up all my calcium. My teeth were falling out one after the other. Anyway I’ve come to see all of it—apart from the love I feel for him—as a biological fluke. I lost all the blood in my body and I lost it twice. He was birthed using these horrible forceps: an enormously big little body. You’re so pretty, I said. I had to stay in the clinic for seventeen days. In the house we slept in the same room because he didn’t want to sleep alone. And I couldn’t sleep alone either, being half-mezmerized by my child. So I was terribly selfish; I didn’t want anyone else to hold his hands. My husband, he played sick and said he was in the hospital. That’s what people say, it doesn’t matter to me, but anyway he was fine and had simply decided not to come by the house. When I was five months pregnant he left and never came back because he’d fallen in love with someone else. I didn’t live as man and wife, that’s the truth. I worked and got home late and my son didn’t sleep waiting up for me. So that’s how he was raised until he was four.

I’d drop Carlos off at school and cry like a dummy; I cried every day. A mother with a strong character can be both father and mother. Unfortunately, with that kind of pressure and all the bad things and the bad birth, all that influenced what happened afterward. Because, after my father died, I had to take on more responsibilities that one should at that age. For me, solitude is the best companion, I can mull things over. My husband and I, we lived a whole life together. When he left my mind was like a biographer. When he left I wrote a poem. Then I started to cry, to cry a lot, and then to write another poem because I felt more grief. But with all this time we’ve been separated—they say that love shortens distance—we’ve also become more honest with each other.

If I die Carlos is going to suffer, and if he were to die I would suffer unspeakably. I think I would have no reason to live, and the only thing I would ask God is if we might die the same day so that neither one nor the other suffers. Because just thinking about it I become desperate. I go crazy. And this whole nervous condition I have is due to thinking so much about him. When I start thinking about my life, I think of suffering more that I should have, and then of being so happy, for having loved him so much. On his birthday, our first birthday, that was his first cake. On Sundays I took him to Mass, and afterwards I’d carry him to the Plaza de Armas, which is traditional with kids, to buy balloons, feel the music, watch the other kids. A lot of people think that the only end to bitterness is suicide, but I say no, suicide doesn’t lead to anything. It’s not bravery or cowardice, it’s mental derangement. You can’t know how much you hurt others, making that choice. I think it’s the saddest choice a person can make.

SITE MAP

Three hospital tables appear on the Site Map for Sala de Espera, on top of which Leppe installs three monitors, together with their respective playback mechanisms. Each of the three channels contains a partial version of a unified piece, previously produced, known as Las Cantatrices. A fourth monitor, also on a medical stand, plays a video of Leppe’s mother describing his birth and the first years of his childhood. Las Cantatrices should be recognized as both an autonomous piece, made by this conjunction of four monitors, and as part of a larger installation that, when arranged following the site drawings, comes together in a single space as the video-installation known as Sala de Espera.

AN “INSTALLATION OF INSTALLATIONS”

Sala de Espera is an installation of installations, each one with its own mini-diagram and each in dialogue with the larger diagram of Carlos Leppe’s body of work during this period, works defined by the publication of the book Cuerpo correccional, written by Nelly Richard and presented in sur Gallery on November 30, 1980. The book’s role in “defining” Leppe’s work is confirmed by the place that the book’s cover image occupies in the space: arranged on the wall close to the entrance to the room, behind a stand holding the slide projector that reproduces, on the facing screen, the single image of Leppe as a child, seated in a park with his mother. Five bundles of soil have been arranged at the foot of this screen, each the size of a body and wrapped in thick, transparent plastic. [1]

The stand with the slide projector, the image of the book cover, the back cover of the book, the screen, the image of the mother, and the bundled soil: all this forms a mini-installation. We will refer to it as La Portada, and it intersects on the site map with Las Cantatrices. However, on the same side of the room as La Portada, a third mini-installation is also present, which will we call El Título and which is formed by a stand that holds a basic television set, tuned to the state channel and playing the day’s programming, but with the sound on mute. Barely a meter away, resting on the floor at a diagonal, Leppe places the carcass of a huge old television, the earliest kind to be made in Chile. Inside, he has arranged a scene of the Immaculate Conception, framed by a Christmas wreath. The interior of the carcass is reinforced by a sticky material, made from a straw and mud base, for which Leppe himself called the object the “mud video.” Finally, above the stand that holds the working television, Leppe hangs from the ceiling the words Sala de Espera, written in neon lettering.

There is a factor common to the three mini-installations, and which operates as a unifying element, sustaining a continuity and completeness of the installation when taken as a whole. This element is the network of connected fluorescent tubes, along with their respective frames, which Leppe distributes across the walls and floor of the room.

Sala de Espera [2] is not a performance art action, but rather a complex installation formed by three mini-scenes, one of which reproduces an art action and therefore comes to occupy the principle space. The two remaining mini-scenes are secondary, as they are designed to supply contextual elements, taking up the themes of what is recorded and considered in Las Cantatrices. These two secondary, mini-installations also function as sites where a specific publishing debate unfolds, that between an authorial politics La Portada and a public politics El Título.

La Portada, as a mini-installation, contains a photographic reproduction what can be considered a key antecedent to Sala de Espera: the intervention on the steps. The fluorescent tubes are themselves also transported to the exhibition space and provide, with their cables and support frames, a luminosity reminiscent of a factory space (meaning, a non-domestic space), though their placement does not seem to correspond to any predictable pattern.

Sala de Espera can be conceived as a “staging” of the text in Cuerpo correccional, by Nelly Richard. However, the book is itself already a theoretical staging of Leppe’s own work, from which the book precedes. The four-channel video montage of Las Cantatrices can be considered the generative moment. From the beginning, the video montage was conceived as an object of future analysis, whose theoretical support would be a book in which photographs of the piece in-process would play a central role. To that end, Sala de Espera is an installation created with the specific intention of supporting the launch of two books: Del Espacio de acá, by Ronald Kay, and Cuerpo correccional, by Richard, though the installation cannot be understood, except in a speculative sense, in relation to a show of Dittborn’s, in which he included some of the work mentioned in Kay’s book. This lends credence to the hypothesis that Leppe’s installation is a visualization of Richard’s book, with Dittborn’s exhibit as an “illustration” of Kay’s thesis. That difference constitutes a polemic moment, what in Leppe’s case will situate Dittborn, whose work pertains to the representational side of art, as a “reformist artist,” while Leppe’s work with his own body insists on a kind of presence of the work that radicalizes, both in terms of medium and manner of expression, via pieces that interpolate the texts and strain the conditions of their interpretability.

Sala de Espera is a large installation delineated by three mini-installations, which we have called Las Cantatrices, La Portada, and El Título (See Site Map). In the first, the image of Leppe’s mother, telling a story, faces a triptych of operatic enunciation that puts front and center the orthopedic instrument keeping Leppe’s mouth open. Through its grasp, Leppe simulates the singing of a lyric aria, a formalized instance of regulated sentimentality. In the second, the cover image of Richard’s book, which shows Leppe’s installation on the steps to his childhood home (the origin of the discourse), an installation itself conceptualized so that its documentation could serve as the book’s cover. Said image is expanded upon by the projection of a second image, a photograph of the mother and son sitting on the grass in a public park. In the third installation, the distinction between public and private is recreated to reverberate in the terrain of media, with Leppe contrasting the hot residue of popular religious culture with the cold modernity of religion’s televised representation.

The fluorescent tubes that Leppe scatters across the floor and walls of the room underline his desire to position the installation as a text autonomous from Richard’s book, while also serving as a device that connects the three mini-scenes. This method of making present the visual thinking involved in the installation occurs again, in another luminous moment, through the fluid of the neon writing, which renders the title itself visible. And we should remember, from now on, that all the monitors too are projectors of light, as the images radiate from the back of cathode light tubes.

To further explore the relationships between these pieces, one must further extend the notion of a work’s polemic, putting certain elements in relation to other significant works by the artists, which we have not yet sufficiently taken into account. Consider the simulacra of bodies wrapped in thick plastic, which in fact contains soil, but which visibly suggests the existence of recently excavated remains. Their appearance recalls a few photographs that resulted from an experiment Kay did in 1974 with those attending one of the courses he was giving at the Department of Humanistic Studies at the University of Chile. Said exercise took the name Tentativa Artaud (Tentative Artaud )and was recently exhibited, in 2009, at the MNBA (National Museum of Fine Art). However, those attending the course were members of the literary and art scene of that era, and the work in question was, at the time of Leppe’s installation, sufficiently well-known. Leppe’s decision to incorporate certain objects pre-sanctioned as “art” is an expression of how he conceives of his work, electing for every mise-en-scène to serve as a direct interpolative response to the interpretive hegemony of the art world. In Sala de Espera, the two great contradictories are Dittborn and Kay. Ultimately, their presence only emphasizes the collaborative nature of Leppe’s and Richard’s work during the conceptualization and execution of these pieces. For it is these pieces upon which Cuerpo correccional was based and eventually printed, thanks to the significant editorial support of Francisco Zegers (who ran, at that time, the advertisement agency where Leppe worked as art director).

NOVEMBER 30, 1980

On November 30, 1980, in sur Gallery in Santiago de Chile, two books are presented: Cuerpo correccional, by Nelly Richard, and Del Espacio de acá (From the Space of Here), by Ronald Kay.

Del Espacio de acá is a book that has, as its antecedent, a catalogue which Eugenio Dittborn had edited in 1979 to accompany the exhibition he was anticipating in CAYC (Cento de Arte y Comunicación) in Buenos Aires. However, the exhibition was cancelled by CAYC’s director, Jorge Glusberg, who decided that the political conditions in Argentina—at that time still under dictatorship—did not exist for mounting an exhibition of Dittborn’s work, in what, under a complex conjunction of circumstances, had become directly associated with the detained-disappeared.

For Eugenio Dittborn, the cancellation of the exhibition hit hard. Living then in Santiago de Chile, and having had to live with the detainment and disappearance of many of his friends, he understood perfectly the situation of Jorge Glusberg. However, the cancellation provoked in Dittborn not insignificant frustration, as he had already prepared the exhibition, to the point of having the catalogue printed before going to Argentina to hang the show.

The catalogue is titled N.N.: autopsia (rudimentos teóricos para una visualidad marginal) [N.N.: Autopsy (Theoretical Rudiments for a Visuality from the Margins), 1979] and written by Ronald Kay. It was printed on opaque couché paper, about 40 pages in length, with a front and back cover of carton-pierre and a lithographed cover image; the whole thing is bound with wire. The book is divided into five chapters, and will come to form part of Del Espacio de acá, which Ronald Kay will publish a year later. This second book is divided into three parts: 1. Construction Materials; 2. – Theory; and 3. Painting and Graphic Art, featuring work by Eugenio Dittborn and closing with an appendix written by Dittborn himself, titled Tool Box.

The catalogue N.N. anticipates, in concept, many of the themes in Del Espacio de acá, which is presented on November 30, 1980. In this sense, it bears the advantage of having enumerated the implicit theoretical problems of Dittborn’s work, which are then further developed in the third section of the later book. It should be noted that the later catalogue begins with an epigraph from Dittborn himself, in which explains the methods he used in making the works that appear in the book, as well as an addition of two new chapters to the Theory section: “Time that Splits Itself” and “The Reproduction of the New World.”

The inclusion of the two abovementioned texts serve as evidence of the evolving, polemical context of the Chilean art world between June of 1979 and November of 1980. They allow us to reconstruct this lively context on which the key theoretical concepts holding up Dittborn’s work were based; concepts which, at the same time, were in dispute with Leppe’s work, which emerged at the same juncture.

Cuerpo correccional is the second book to be presented November 30, 1980, in sur Gallery. A crucial question that remains to be asked about the two books is how their difference in theoretical perspective, and the consequences of those affiliations, may have determined the approaches to the collaborations seen between Richard/Leppe and Kay/Dittborn in the late seventies.

Richard and Leppe forge their relationship in 1978, when they collaborate on curatorial and publishing work through Cromo Gallery.

In conceiving of Sala de Espera as an exhibition “it should be noted that the book Cuerpo correccional can be understood as a script or libretto for the installation, an anticipated space. Nelly Richard’s text and its chapter headings were conceived as if written after the mounting of the installation. In this sense, the book fulfills its function within the space of editorial production as an independent, theoretical grounding for the piece, rather than a book or a catalogue.

Regardless, it remains to be determined how much of Cuerpo correccional operates like a book and how much serves as a catalogue. It is a book that intends to be both a description of the exhibition and an analytical platform for the work described. The chapter headings themselves serve strictly to reinforce the theoretical status of Leppe’s previous works, such as El Perchero, La Acción de la Estrella, Las Cantatrices, Objetos anzuelos, Reconstitución de Escena and Happening de las gallinas (respectively, The Perch, the Star Action, The Opera Singers, Hook Objects, Reconstituting a Scene and Happening for Chickens).

The Chilean art world remains largely unaware of the fact that two books were presented “in accompaniment”with the objects to which the authors referred in their critical texts. Further, that said presentation was organized by a recognized thinker—Patricio Marchant—who read a text alluding to a discourse that went beyond the aims of the presented books. Nor should we forget that both Patricio Marchant and Ronald Kay, at that moment, were professors of Humanistic Studies at the Engineering School of the University of Chile.

That November 30, 1981, Patricio Marchant read Discurso contra los ingleses [3] (Statement Against the English) at the opening of Leppe’s and Dittborn’s exhibition. This last point must be reconstructed to appreciate the extent to which work as polemic was understood by both artists. Thus, a detailed study of this argument must take all the elements linked to the construction of Sala de Espera into account. However, such elements occupy a difficult space, problematized by the distance at which they are encountered and the differentiated space of their claims. They also point toward the kind of relationship that exists between a book like Del Espacio de acá and Dittborn’s work, in strict terms. However, using Dittborn/Kay as an analogous example, some critics have suggested that Cuerpo correccional, with respect to Leppe’s work, functions in an inverse relationship, in which the situation of textuality and the work correspond to a kind of collaborative production that can be distinguished from the dependence that Dittborn’s work might have with respect to Kay’s “theory of photography,” a theory Ronald Kay had elaborated independently and prior to coming into contact with Dittborn’s work.[4]

In Sala de Espera, the conceptual and political character that, in 1980, must have accompanied the development of a book such as Cuerpo correccional, brings with it some implications that bolster the hypothesis that the book should be understood as an “editorial installation,” with Sala de Espera as its material expansion. All that resonates in the reception of both objects in the controversial scene of 1980, above all, in artistic sectors close to the Workshop of Visual Artists (Taller de Artes Visuales, TAV), which felt affronted by the economic means available to Leppe and Richard for installing the work they had produced. Some objected to the use of sophisticated materials—particularly video-recording technology and neon light—and, above all, to the fact that the book was printed on couché paper and its cover on King James heavy cardstock, materials that contrast violently with what was left over by the “flimsy mimeographs” of the Chilean left.

These flimsy graphics had already become the object of Leppe’s attention, from the moment he gained charge of the graphic design of the catalogues of Cromo Gallery, where Nelly Richard served as director from 1978-1979. All the catalogues were printed in offset, on “legal” dimensions, simulating technical aspects of mimeograph printing. Such procedures would be used by the Dittborn editions at the same moment, so that the particular editions of both the Kay and Richard books implied a politico-technological swipe at the social vision of art world leftism.

An analogous rejection had to do with the use of fluorescent and neon light in the installations and actions of Leppe. They were callously associated with “consumerism” by a reaction of some associated with the TAV, which in that moment brought artists who had been dismissed by the University of Chile together with artists shut out from other organizations. And yet, Leppe was the first to incorporate neon and fluorescent lights into his work, appealing to the need to reveal zones of “great luminosity” as much as the existence of their counterpart, zones of “great darkness” that destroy the social sphere. In that light, the shine of the tiles and the allusion to hospital spaces acquire value as an artistic choice, in depicting what a Sala de Espera looks like or might mean, as if situating the contaminated social environment in a larger prophylactic universe.

CUERPO CORRECIONAL AS AN EDITORIAL INSTALLATION

Cuerpo correccional is not a catalogue, but rather a book that aims to fix its status somewhere between an artist’s book and a book about an artist. In the former, the book is an apparatus for artistic production, which is to say, it cannot be reduced to a medium for the reproduction of work that already exists. In the second, the written work falls into two possible categories: either the book adheres to the norms that define a book as printed, regular blocks of text, in which what we identify as its content refers to a specific object, susceptible to being conveniently illustrated; or, alternatively, the book plays with the possibility of acquiring, on the page, the same “visual weight” as that of the art objects discussed. To put it another way, the layout suggests a possible return to visuality over legibility, establishing a space of graphic tension that will strongly determine any reading. Richard’s book situates itself between the two categories, the conceit of its layout allowing graphic weight to function as the epistemological support of a specific scripto-visual analytic destined to influence the recomposition of the Chilean art world at this particular juncture at the end of the 1970s.

To understand the radical turn of Cuerpo correccional is precisely to take stock of the dominant publishing mode for the cultural and political left, an approach sentimentally and semantically subordinate to the stencil. That is to say, this world thought in terms of terms of layout formats, in mimeograph paper, official dimensions, with a metallic hook holding the pages together at the upper-left hand corner, in what has come to be called “the plenary report aesthetic.” The term refers, obviously, to the plenary meetings of the Central Committee. But it is also a “reform report aesthetic,” meaning the documents associated with the University Reform movement in Chile. This report aesthetic extended even to academic editions, above all in the Social Sciences, where it became customary to publish, on mimeograph paper, booklets about research advancements, placed between two sleeves or cardstock title pages, with a cover printed with a manufacturing die, which displays the report’s title and the name of the author. This aesthetic is taken up by Carlos Leppe as a possible approach for catalogues, an idea that first appears in relation to his work in 1977.

The cover of Cuerpo correccional, however, was printed on King James cardstock, weighing over 200 grams, glossy on the front and matte on the reverse. If the publishing conditions of the cultural left were subordinated to a stencil aesthetic, one can only imagine the violent symbolism of the book’s appearance for this sector. Since the look of Cuerpo correccional displayed the formal characteristics of a banker’s report, printed in the highest publishing standards of the era, the gloss of the cardstock was perceived as an implicit compromise with the political economy of the military regime. The gloss was perceived as mannerist affect, chosen by artistic actors compromised by the market, while the matte reports on mimeograph paper could be understood as the austere expression of a “true” analytic that distilled a certain historical reality. This reaction indicates the extreme exactitude then present on the left, which attributed political validity to a report for transcribed on mimeograph paper. Simply put, it was beside the point. The left had gotten stuck in an older stage of development of its forces of production.

We might wonder, then, why the title and name on the cover are printed in lowercase, as if to say, “low-level print job.” The typography, expressing itself as a diminishment, seems to function as a center of supplementary excess, regulated by the edges between the steps of the staircase, framed by two lines of fluorescent tubes, the brightness of which is made equivalent to the emptiness of the permeable letters, against which one can glimpse the binding of the book, covered by the printed photograph, to suggest both a literal and figurative lapse.

But the title of the book and the name of the author are printed over black ink that recreates the iconic darkness of the first two steps. This emptiness points to the subject matter of the work, marking “the lowly.” Over the width of the line of the words Cuerpo correccional the glowing lines delineate the above and below of the image, emphasized by where the photograph was cropped. What more, the parallels are cut off, 23 centimeters above, at the top of the page. The indicated space between above and below is the representation of a point of access, implying both an ascent and a descent.

Let’s turn to the next page. A small graphic tactic on the inside jacket:

“The photograph on the cover of this book documents an intervention made at the home of Catalina Arroyo, mother of the artist, at Seminario 960, Santiago de Chile, and which illuminated the access stairwell for the building for a full 24 hours.”

Let’s open the jacket cover to unfold and expand the cover image to the right, with the intention of producing the first double page. Said unfolding gives space to a configuration that defines the distribution of the interior surface of the book: the page on the right, for the photograph; the page on the right, to recoup the already-signaled textuality. Just as, from pages 18 to 97, the regular sequence of text and image gives way to the suspicion that with respect to every page on the right-hand side, where the text is printed, the following page—where the photographs are printed, to be explained on the page further following that—operates like an illusory sustainment of textuality, as if the photograph came after the word. Or rather, as if the photograph were based on whatever text appears just before it. But this is not the case, because one double spread of pages follows another, and so on, until it succeeds in reversing the hypothesis, one page becoming instead a recognizable “negative” of the other.

With this discovery of unfolding the flap, the cover turns into a kind of left page, while what was the inside jacket takes on instead the role of a supporting text that operates almost like marginalia. The note, adjacent, unfolds like a substitute for something that escaped its explicit function, presenting instead only as an epigraph that anticipates the title page of the book, in which can be read, black on white, Cuerpo correccional, Nelly Richard.

In most published books, where the image is presented as an invasive occupier of space, the text—as imaginal space—is often, in most cases, expected to fill the bottom of the page. The image seems to illustrate it, fulfilling a pre/written role, while the text is taken to be a device that controls the effectiveness of that expansion. But here, then, is the book jacket flap, in its jacket dimensions, exhibiting a practically permanent mark, the parallel line that permits us to see and locate the jacket as “behind” the cover, and whose function, accomplished with a centimeter of give, is to permit the jacket to get folded a second time, not yet for marking a page—which will happen eventually—but rather to envelop the entire book.

The jacket cover of Cuerpo correccional has come to acquire the unexpected function of a double armor for the text, and, though at one moment could be considered either footnote or marginalia, has turned into an epilogue. But an epilogue that invades, “writing over” the back cover. The “photographic document of the front cover” overlays itself on the photographic document of the back cover: the washed-out reproduction of an image of graffiti, as if commenting on, with a sense of parody, the public space of inscription of a graphic that doesn’t quite constitute as a word. Cover and back cover support each other, both framing photographs that point, in the first case, to a specific authorial intervention, and, in the second, to an authorship dissolved by the collectivity of a wall graph. The value of the expanding front cover is strategic—in its ability to wrap around, cover over—introducing us to the back cover, only to banish it from our memory.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A.- Magazines and Newspaper Articles:

— Ana María Foxley, “Psicoanálisis artístico” in Hoy, November 26-December 2, 1980, 51.

— Fernando Balcells, “La separación de las aguas en el arte” in La Bicicleta, nº 10 (Marzo-abril 1981), 21.

— Nelly Richard, “Dal Cile Sul Cile”, Revista DOMUS nº616, April, 1981, Milán.

B.- Theoretical texts on Latin America, which explicitly mention Sala de Espera:

— Gustavo Buntinx, “The return of the Sign: The Resymbolization of the Real in Carlos Leppe´s Performance Work,” in Over Here. International Perspectives on Art and Culture, ed. Gerardo Mosquera and Jean Fisher (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Pres, 2004, 320).

C.- Photographic Documentation, or media in which Sala de Espera has been reproduced:

— Nelly Richard, “Dal Cile Sul Cile”, Revista DOMUS nº616, April, 1981, Milán.

— Revista Art Press nº62, September, 1982.

— Milan Ivelic y Gaspar Galaz, Chile, arte actual, Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, 1988, p.200.

— Carlos Leppe, Cegado por el oro, Galería Tomás Andreu, Santiago, Chile, 1998, pp.24-25.

— Gerardo Mosquera, Copiar el Edén: Arte reciente en Chile, Ediciones Puro Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2006, pp.414-415.

— Gustavo Buntinx, Op. Cit., p.31.

D.- Canonical Texts:

— Ronald Kay, Del espacio de acá: señales para una mirada americana, Editores Asociados, Santiago, Chile, 1980.

— Nelly Richard, Cuerpo correccional, V.I.S.U.A.L., Santiago, Chile, 1980.

Footnotes

[1] Adriana Valdés wrote a column in La Separata based on this photograph.

[2] Carlos Leppe / Justo Pastor Mellado, Sala de Espera, en Cegado por el oro, galería Tomas Andreu, Santiago de Chile, 1998.

[3] Patricio Marchant, discurso contra los ingleses.

[4] Paula Honorato “sujeto biográfico y sujeto histórico en Sala de Espera de Carlos Leppe”.